Normally I scoff at folks who are too quick to dismiss the Roman numerals as cumbersome or awkward. Any cultural thing that survives more-or-less intact for a couple millennia surely has some value for the people who use it. And no one at the time seems to have complained about the Roman numerals, even when other (Greek, Indian, Arabic) options were known. That pastime only came about in the 18th century, by which time the Roman numerals were already archaic.

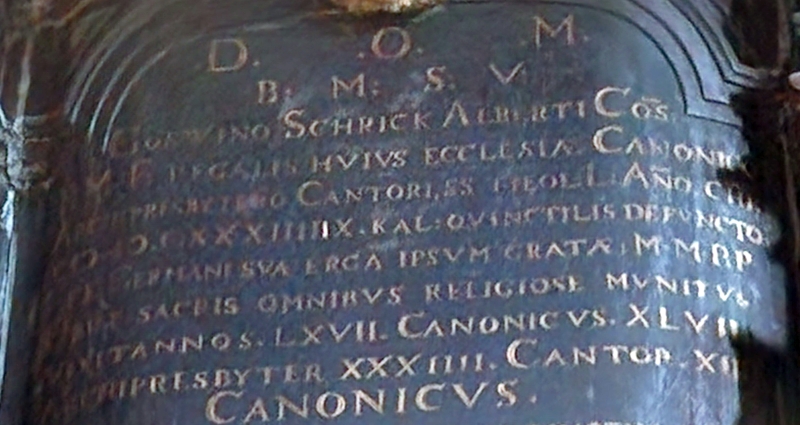

But I’m willing to grant that the following inscription, from St. Nikolaus’ chapel in the cathedral at Aachen, tests my resilience on the point. I was recently on holiday in Europe and took the following photo a couple weeks ago:

Right there in the middle, on the fourth line of the main text, appears to be a date of CIↃ.IↃ.CXXXIIIIIX. The first bits are just old-fashioned signs for M=1000 and D=500 (and I’ll transcribe them as such hereafter). The CXXX is straightforward as 130. But IIIIIX instead of V for 5 is a new one to me. Actually, it’s the only example of that anywhere that I know of. But the reading of 1635 is definitely right, from context, representing the year of the death of Goswin Schrick. So what’s going on?

We can rule out that the writer didn’t know the sign V for 5, which is elsewhere in the text. Theoretically, one might extend a line of text by using a longer form of a word or numeral than needed, but this text is full of abbreviations already, so it hardly seems likely that they’d have chosen this as the one place to conspicuously use a surfeit of signs. And I’ll just assure you that while IX was common, and IIX not too rare, and I even know of a couple where IIIX = 7, IIIIIX is a complete one-off (a hapax legomenon, if you want to be fancy about it).

The first trick is that the final X isn’t actually part of the numeral, but attaches to the following word ‘KAL’, which is an abbreviation for ‘kalendas’, or the calends of ‘Quinctilis’ which in this case is the fifth month of the Julian calendar, July. So the year is actually 1635, MDCXXXIIIII, X (10) before the calends of July, or June 21, 1635. I was pretty confused myself until I looked the inscription up and found it in the Deutsche Inschriften Online (DIO) here, which transliterates the relevant bit as “M. D. C. XXXIIIII. X. KAL(ENDAS) QVINCTILIS DEFVNCTO”.

Now that got me to thinking. The chapel was pretty dimly lit and the relevant part of the inscription is pretty high, and it’s not like tourists can just climb up on the furniture to get an ideal angle. But I don’t see anything like a punctus / dot between the IIIII and the X, and the professional photo at the DIO website agrees with me:

So we’ve reduced the problem a little, while introducing a new one. Now we just have M.D.CXXXIIIII, but that’s still an awfully weird way to write it, even if it’s not subtractive. So now we need to know why it’s not M.D.CXXXV. But we also need to know why there’s no space or delimiter between the IIIII and the following X. The punctus (‧ or .) was really common in medieval and early modern Roman numerals, as an aid to reading, sort of how we moderns use interdigital commas (1,000,000 vs. 1000000) to make reading easier. You see them in multiple places in this text. And it would be expected exactly where it’s missing, between the IIIII and the X.

Here’s my theory. You know how you forget what year it is, maybe when you’re writing a cheque or dating a form, especially in January, but really, any time of year when you’re tired? Imagine our beleaguered writer, unaware that their error is about to be recorded for all time, and happily chiselling away Is, four of them in fact (IIII and IV were both completely normal at the time, and we see XXXIIII later in the text to confirm it). You might even put a punctus (dot) or space between the XXXIIII and the following X – wouldn’t want to confuse anyone. But then it turns out that old Goswin didn’t die in 1634, and you have a problem. Now, if it were me, I might try to finagle my I into a V by adding a / on the right hand side, like how you change a D into an A on an errant report card:

But in this case, I think someone added a fifth I in the space before the X, or (if there was a punctus to begin with) turning the delimiting mark into an I. I think you can see in my photo (taken from below) that the fifth I looks a little bit different -the light shines differently against it. I suspect it was added in later to correct the date, but with the consequence that it ended up merging the sequence of Is with the X for the day. So what we’re seeing here is a scribal emendation that, unfortunately, solves the problem in a way that (I’ll grant) is pretty cumbersome.

Now here’s the kicker. I went to the cathedral at Aachen specifically to look for this inscription; my family thoughtfully tolerated my many quirks throughout the holiday, which involved taking photos of strange inscriptions while they looked at glorious architecture. But I had seen a description of this inscription in a 19th century book that (unlike the DIO, which got it right) bizarrely went even further, and put the date as 1634: M.D.CXXXIIIIIIX (!!!!!!), with six Is followed by an X. That, (un?)fortunately, seems to have been an error by the 19th century antiquarian. But for more on that error-prone scholar, and the broader Sooper Seekrit numerals project that was agglomerated into my European vacation, you’ll have to wait a bit longer. No more than IIIIIX weeks, I promise.