For several years I have been deeply concerned with the proliferation of pseudoscience in anthropology. In 2007 I had the remarkable opportunity to teach a seminar on pseudoarchaeology, leading to the Pseudoarchaeology Research Archive. Of particular interest and concern to me is the use and misuse of inscriptional evidence in pseudoarchaeology, because few archaeologists have any expertise in linguistics, and few linguists have any expertise in archaeology. For instance, it is impossible to deal adequately with the work of the late Barry Fell without the ability to work with both sets of methods and data. Given this blog’s focus on the intersection of linguistic and archaeological anthropology, you should expect to read quite a bit about this subject here. Perhaps someday I’ll even write that article on Barry Fell’s cult of masculinity that I’d been meaning to put together.

There is probably no culture or language that has attracted more pseudoscientific attention than Basque. As a language isolate, the ongoing quest to understand the origins and possible cultural affiliations of the Basques, so thoroughly European and yet so foreign, has attracted incredible scholarly attention over the past century and more, with molecular genetics now added to the mix of material culture and historical linguistics as part of the often-misemployed ‘race-language-culture’ triad. One of the more popular theories among some scholars (particularly the geneticists) is that the Basques are the remnants of Paleolithic peoples in Europe who were largely replaced by the Indo-Europeans. This basically relies on the fact that the Basques have higher percentages of certain genetic markers than their neighbours, but there is no other reason to believe that it is true.

Yet there is very minimal textual evidence for the Basque language prior to the eleventh century CE, making it very hard to trace Basque history (and, a fortiori, its prehistory). There are several hundred personal, deity and place-names recorded in Roman inscriptions in a probably-related language called Aquitainian, dating to the 2nd century CE, but no full texts or even phrases. Until 2006, that is, when reports surfaced that a group of 270 inscribed pieces of 3rd and 4th century CE pottery, glass, and brick had been found at the site of Iruña-Veleia in the Basque country with what was clearly Basque(oid) language (see articles here and here).

You will note that the response was not exactly enthusiastic from the academic community. I recall reading the blog post at Language Hat (the second link) and thinking, “Huh, yeah, probably fakes.” This is quite simply the only rational strategy in a field that has been riddled with pseudoscientific language comparison, through the late Dr. Fell’s Epigraphic Society and its claims for widespread pre-Roman transatlantic commerce, through the pseudoarchaeologist Marija Gimbutas’ pseudo-feminist Indo-Europeanism, and many others. And the find was so perfect – evidence not only that Basque was written in the 3rd century CE in quantity, but that the Basques were Christians at a time when most of Western Europe was not. And so when nothing was published following this ‘finding’, and no photos given anywhere (not even in the media) of any of the artifacts, I was neither surprised nor overly disappointed, and presumed that the initial reports were exaggerated and at best, that some new Aquitanian names had been found.

And indeed, word has come out this week in the Guardian that the whole thing is not only a fraud, but a hoax of the most preposterous degree. For instance:

– The glue used on some of the artifacts is apparently modern.

– The Calvary scene depicting the crucified Jesus apparently contains the inscription ‘R.I.P.’, essentially endorsing the heresy that Jesus did not rise from the dead but in fact was dead.

– The presence of (purportedly) Egyptian hieroglyphic writing (essentially extinct by the time) alongside the expected texts in Latin script (recording both Latin and Basque language). This leads to the claim that “The hieroglyphics caused speculation about the existence of third century Egyptologists who might have created the inscriptions to teach children.”

– References to the Egyptian Queen Nefertiti and to the 17th century philosopher Rene Descartes (!!!).

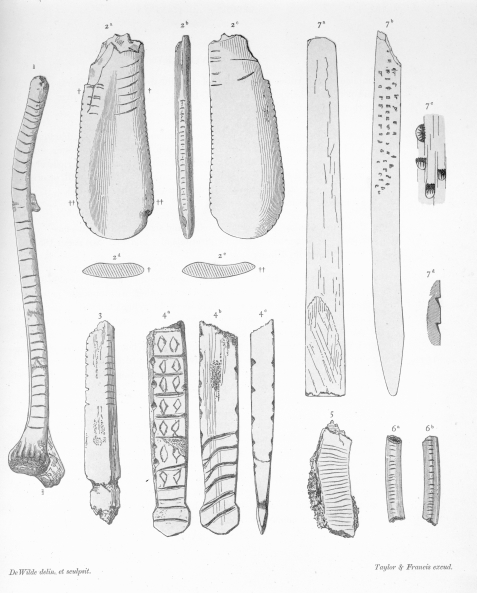

Now, this is not the first time that a preposterous hoax has been perpetrated. The Davenport tablets ‘excavated’ in Iowa in 1877 exhibit similarly ridiculous characteristics. But given the degree of scrutiny to which archaeological finds are exposed these days, and given the demands for publication, and the risk to the professional reputation of the excavator, such a shoddy hoax is difficult to explain. For his part, the excavator, Eliseo Gil, is maintaining that the finds are genuine (article in Spanish), although if even half of what has come to light is true, this is an utter hoax. Could we have a new affaire Glozel in the making? Not unless things are much muddier than they now seem to be.