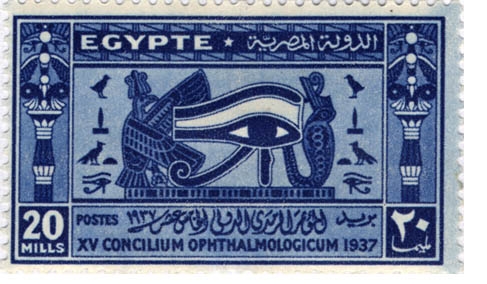

Well, it only took about 20 minutes for Dan Milton to solve the mystery of the Egyptian stamp: it has four distinct numerical notation systems on it: Western (Hindu-Arabic) numerals, Arabic numerals, Roman numerals, and most prominently but obscurely, the ‘Eye of Horus’ which served, in some instances, as fractional values in the Egyptian hieroglyphs:

At the time I posted it this morning, it was the only postage stamp I knew of to contain four numerical notation systems. (As Frédéric Grosshans quickly noted, however, a few of the stamps of the Indian state of Hyderabad from the late 19th century contain Western, Arabic, Devanagari, and Telugu numerals, and also meet that criterion, although all four of those systems are closely related to one another, whereas the Roman numerals and the Egyptian fractional numerals are not closely related to the Western or Arabic systems. So that’s kind of neat. I have a little collection of stamps with weird numerical systems (like Ethiopic or Brahmi), multiple numeral systems (like the above), unorthodox Roman numerals (Pot 1999), etc., and am looking to expand it, since it is a fairly delimited set and, as a pretty odd basis for a collection, isn’t going to break the bank. In case I have any fans who are looking for a cheap present for me. Just sayin’ …

At the time I posted it this morning, it was the only postage stamp I knew of to contain four numerical notation systems. (As Frédéric Grosshans quickly noted, however, a few of the stamps of the Indian state of Hyderabad from the late 19th century contain Western, Arabic, Devanagari, and Telugu numerals, and also meet that criterion, although all four of those systems are closely related to one another, whereas the Roman numerals and the Egyptian fractional numerals are not closely related to the Western or Arabic systems. So that’s kind of neat. I have a little collection of stamps with weird numerical systems (like Ethiopic or Brahmi), multiple numeral systems (like the above), unorthodox Roman numerals (Pot 1999), etc., and am looking to expand it, since it is a fairly delimited set and, as a pretty odd basis for a collection, isn’t going to break the bank. In case I have any fans who are looking for a cheap present for me. Just sayin’ …

We in the West tend to take for granted, today, that really there is only one numerical system worthy of attention, the Western or Hindu-Arabic system, which is normatively universal and standardized throughout the world. We also tend to feel the same way about, for instance, the Gregorian calendar. That’s a little sad but not that surprising. But we also take it for granted that, in general, throughout history, each speech community has only one set of number words, one script, and one associated numerical notation system. Of course, a moment’s reflection shows us this isn’t true: virtually any academic book still has its prefatory material paginated in Roman numerals, not to mention that we use Roman numerals for enumerating things we consider important or prestigious, like kings, popes, Super Bowls, and ophthalmological congresses. And this is not to mention other systems like binary, hexadecimal, or the fascinating colour-based system for indicating the resistance value of resistors. I’ve complained elsewhere that we put too much emphasis on comparing one system’s structure negatively against another, but to turn it around, we should ask what positive social, cognitive, or technical values are served by having multiple systems available for use.

We need to be more aware that the simultaneous use of multiple scripts, and multiple numeral systems, simultaneously in a given society is not particularly anomalous. In Numerical Notation (Chrisomalis 2010), I structured the book system by system, rather than society by society, which helps outline the structure and history of each individual representational tradition, and to organize them into phylogenies or families. But one of the potential pitfalls of this approach is that it de-emphasizes the coexistence of systems and their use by the same individuals at the same time by under-stressing how these are actually used, and how often they overlap. Just as sociolinguists have increasingly recognized the value of register choice within speech communities, we ought to think about script choice (Sebba 2009) in the same way. With numerals, we also have the choice to not use number symbols at all but instead to write them out lexically, which then raises further questions (is it two thousand thirteen or twenty thirteen?) – many languages have parallel numeral systems (Ahlers 2012; Bender and Beller 2007). We need to get over the idea that it is natural or good or even typical for a society to have a single language with a single script and a single numerical system, because in fact that’s the exception rather than the norm.

The stamp above is a quadrilingual text (French, Arabic, Latin, Egyptian) in three scripts (Roman, Arabic, hieroglyphic) and four numerical notations (Western, Arabic, Roman, Egyptian). We should think about the difficulty of composing and designing such a linguistically complex text – it really is impressive in its own right. We should also reflect on the social context in which the language of a colonizer (French), the language of the populace (Arabic), and two consciously archaic languages (Latin and Egyptian), and their corresponding notations, evoke a complex history in a single text. Once we start to become aware of the frequency of multiple languages, scripts, and numeral systems within a single social context, we have taken an important step towards analyzing social and linguistic variation in these traditions.

Ahlers, Jocelyn C. 2012. “Two Eights Make Sixteen Beads: Historical and Contemporary Ethnography in Language Revitalization.” International Journal of American Linguistics no. 78 (4):533-555.

Bender, Andrea, and Sieghard Beller. 2007. “Counting in Tongan: The traditional number systems and their cognitive implications.” Journal of Cognition and Culture no. 7 (3-4):3-4.

Chrisomalis, Stephen. 2010. Numerical Notation: A Comparative History. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Pot, Hessel. 1999. “Roman numerals.” The Mathematical Intelligencer no. 21 (3):80.

Sebba, Mark. 2009. “Sociolinguistic approaches to writing systems research.” Writing Systems Research no. 1 (1):35-49.