If you’re one of the folks who follows me over on Bluesky (which, by the way, is a pretty cool place for nerds to gather; come check it out!) I’ve been promising a Sooper Seekrit project for weeks, throughout my European vacation. Turns out those two things are related! I spent the last two weeks on family vacation throughout Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg, touring museums and historical sites at a pace that exhausts almost everyone who sees the photos. And while I assuredly did take pictures of the usual tourist things, I figure someone else has taken a better picture of those than I would have. So what, pray tell, was I up to?

One word: chronograms.

A chronogram is a text (usually a line or two at most) that encodes a culturally meaningful date in numeral-signs that also serve as letters. In India and the Middle East, alphasyllabic or alphabetic numerals are used, but in early modern Europe, Roman numeral chronograms were all the rage, using the ordinary Roman numerals MDCLXVI both as numerals and as alphabetic letters, usually marking the numerals specially by making them larger or a different colour. So, for instance (my all-time favourite chronogrammatic composition) I noted that the American electoral year 2016 could be encoded as seXIst Mr. trVMp because X+I+M+V+M = 2016. (U and V both count for 5, and I and J both count for 1, in chronogrammatic practice.) And this is exactly the kind of thing they were used for in Europe: to celebrate, or denigrate, a person’s accomplishments, to memorialize the founding of a place, and so on. Why just stick a date on a cornerstone when you can do it up in semi-cryptic gold letters?:

A few years ago I had agreed to contribute to an edited book after a fantastic Making a Mark conference at Brown. However, I was unhappy with the fit between the (fairly generic, not really new) presentation I gave there, and the volume’s focus on hidden, secret or other sorts of unusual writing. That’s when I remembered chronograms, and the idea I had had years ago. See, back in the late 19th century, a monomaniacal antiquarian named James Hilton (1815-1907) spent the better part of two decades collecting chronograms, publishing three giant volumes on the subject (Hilton 1882, 1885, 1895) and collecting thousands more that he never published (still held in the British Library). He seems to have been a delightful weirdo, almost entirely theoretically disinclined, a wonderful collector. But with three volumes of inscriptions, all with dates (almost by definition) and most with provenience, I saw an opportunity for a professional numbers guy to step in and do some analysis. Using a mix of theories ranging from cultural evolution to verbal art, I compared the Roman numeral chronograms to the other (Middle Eastern / South Asian) traditions and then did a deep dive on the Hilton corpus, analysing 10342 chronograms across 2681 individual texts. The European tradition has a centuries-long history of development, a craze between roughly 1650-1750, and then a decline into obsolescence. In the end, the book came out in 2021 as The Hidden Language of Graphic Signs, edited by my friends Steve Houston and John Bodel. My chapter (available in preprint form), “Numerals as Letters: Ludic Language in Chronographic Writing” is something I’m very proud of even though it’s a weird little topic.

When my wife suggested that we do a tour of Germany and the Low Countries a few months ago, I didn’t immediately think of chronograms. But for years it’s bugged me that, as obsessive as Hilton was, he surely wasn’t exhaustive. He relied on correspondents and his travels, inevitably. I knew that it was likely that his corpus overrepresented British chronograms and underrepresented Czech and Slovak ones, for instance. All of my analysis was based on what Hilton reported. But how hard would it be, I wondered, to find chronograms that are not in Hilton’s three big books? So I made a point, not of going to places we weren’t otherwise going, but just keeping an eye out, for the telltale signs of chronograms. It would be like Pokemon Go, only instead of imaginary monsters, it would be inscriptions. The areas we were travelling happened to be areas where chronograms were already numerous, so I thought I might find one or two.

Reader, I am pleased to report that it is not hard at all. Over the span of a couple weeks I found 23 chronograms “in the wild” – on buildings, in museums, wherever, and of those, 12 were not in the Hilton corpus (14 including two inscriptions that have two each):

- 001: 1612, Aachen: IaCob breCht patrVo qVInta hIC LVX MartIa sIstIt VIXIt CanonICVs spIrItVs astra petIt

- 002: 1593, Aachen: fataLIs ter qVInta DIes et bIna noVeMbrIs annIs seX natVs septVagInta fVIt

- 003: 1804, Aachen: qVInto IDVs noVeMbrIs Coronato pIa atqVe obseqVIosa CIVItas aqVIsgranensIs gratVlatVr

- 004: 1804, Aachen: Inter ContInVos eXVLtantIs popVLI pLaVsVs aqVIsgranVM IngreDIentI

- 005: 1884, Aachen: MarIa foILane CeterIqVe sanCtI patronI hVIC aeDI sVbVenite restItVtae

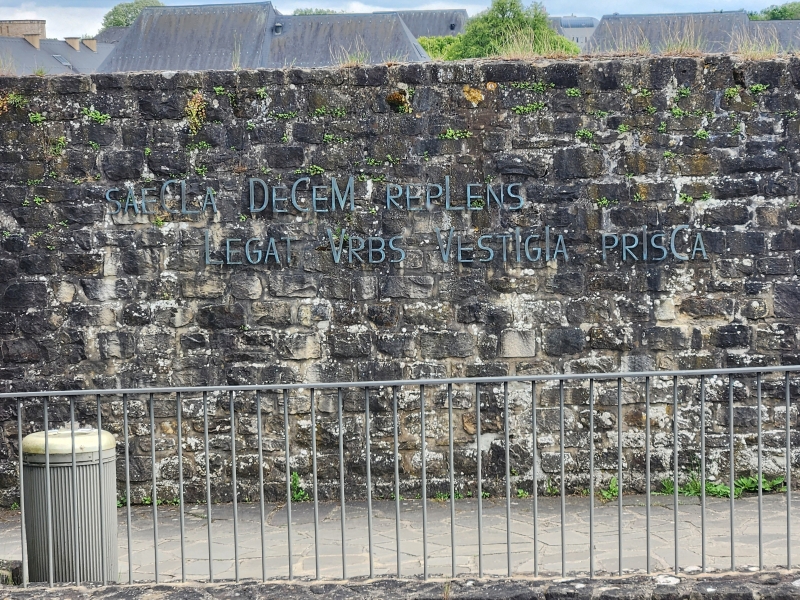

- 006: 1963, Luxembourg: saeCLa DeCeM repLens Legat Vrbs VestIgIa prIsCa

- 007: 1727, Trier: 1) Deo sIbI sVIs VICInIs et posterIs opVs gratVM perfeCere; 2) VrbI et orbI LapIs hIC pIetateM LoqVatVr fVnDatIonIs

- 008: 1738, Trier: 1) DefLorVIt X MartII In aetatIs sVae Vere praenobILIs et InsIgnIs aLtI rVrIs fLos; 2) paLLVIt X aprILIs III februarII eIVsDeM annI orta aLtI rVrIs

- 009: 1720, Brussels: haeC DoMVs Lanea eXaLtatVr

- 010: 1697, Brussels: haeC statVIt pIstor VICtrICIa trophaeI qVo caroLVs pLena LaVDe seCVnDVs oVAT

- 011: 1697, Brussels: hiC qVanDo VIXIt Mira In paVperes pIetate eLVXIt

- 012: 1698, Brussels: aVspICe CaroLo natIonVM ConatIbVs baVaro gVbernante brVXeLLa patesCIt oCeanVs

Now, I don’t think it’s possible to conclude that this ratio of about 50% holds across all periods and regions. Looking at it another way, there are 47 chronograms from Brussels in Hilton’s books; I found another 4. There are 21 from Trier; I found another 2. But frankly I thought that, given how many were already in the books, I wouldn’t find any, just by happenstance.

One of my favourite finds was at what used to be St. Nicholas’s chapel of St. Simeon’s Church in Trier, which now houses the Zur Sim Brasserie overlooking the renowned Porta Nigra. We just happened to stop there for lunch, where surely thousands of people have done so before, and as we were leaving, I found this on the wall (#011 above):

It was one of two places where we happened to eat on our vacation that turned out to have a chronogram (the other being much better-known, on Le Roy d’Espagne in Brussels’ Grand Place). It’s not like no one had ever noticed it before; it’s within sight of a major World Heritage Site. But I could only find one place in print discussing it: here (p. 130-131), in an 1100+ page German book on the archdiocese of Trier. Anyway once I found that one, my family knew they were doomed (in the way that all nerdy families eventually learn). And eventually, I found my favourite new chronogram of all (#012, above), in Brussels, at the Musée de la Ville. You might say, as my wife suggested, that it’s a … groundbreaking discovery. Or even that I’ve been afraid of being … scooped (I’m so sorry):

This is a silver ceremonial spade from 1698 created to commemorate the beginning of work on the canal from Brussels to the Sambre river. Like most such objects, it has clearly never touched dirt, but it is exquisite. My photo (through glass) doesn’t do it justice, but you can see the online museum record here for much better photos (but not mentioning that it has a chronogram). You just have to imagine me hopping about taking about a dozen photos of a freaking shovel. But chronograms, while common on inscriptions on stone, or on medals and coins, or in books, are rare on other sorts of artifacts. So yeah, I liked the shovel; got a problem with that? My wife, who works as an archivist professionally at an institution that has a number of non-chronogrammatic spades from various groundbreaking ceremonies, acknowledged that this one was cooler.

Anyway, if I were to discuss every one of the inscriptions above, this post would be far too long, so let me wrap up with another favourite (#006 above), this one from Luxembourg, on the Bock Casemates, marking 1000 years of the city’s history (963 to 1963):

Twentieth-century chronograms are rare and almost always invoke a much earlier history. But this is undoubtedly a modern chronogram in a modern font. And the message is clear: saecla decem replens legat urbs vestigia prisca; or, roughly “Filling ten centuries, the city leaves us its ancient vestiges.” It does indeed. Hilton, having been dead for 56 years at the time, can be excused for not having this one in his books.

As the title of my post suggests, I did not “catch ’em all”, not even all of the ones in the cities I visited. I didn’t try. But surely the fact that I could find a dozen without even going out of my way suggests that, like Pokemon, there are a lot more out there to be found. So if you live anywhere in Europe (especially Germany, Austria, Benelux, but also Czechia, Hungary, northern Italy, eastern France) in a place that has lots of surviving 17th / 18th century buildings, you can play along too! Feel free to comment with photos of your favourite chronograms and I’ll tell you what I know about them. After all, why should James Hilton and I have all the fun?

References

Chrisomalis, Stephen. 2021. Numerals as letters: ludic language in chronographic writing. In The Hidden Language of Graphic Signs: Cryptic Writing and Meaningful Marks, Stephen Houston and John Bodel, eds, pp. 126-156. New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108886505.009

Hilton, James. 1882. Chronograms, 5000 and more in number excerpted out of various authors and collected at many places. London: E. Stock.

Hilton, James. 1885. Chronograms continued and concluded, more than 5000 in number. London: E. Stock.

Hilton, James. 1895. Chronograms collected since the publication of the two preceding volumes. London: E. Stock.