As you may know, my dad, Peter Chrisomalis, was an educator throughout his career, working as a classroom teacher and later as a school principal until his retirement. And, as surely everyone knows, educators value the three Rs: reading, riting, and rithmetic. But also, as I desperately hope everyone knows, and as the educators reading this might rightly complain, two of those words do not actually start with R. So I don’t want to talk about those three Rs today, in talking about my dad, who passed away yesterday (Dec. 16) at the age of 83. Instead, I’ve got three very different Rs for you, ones that you probably don’t know, but at least they actually do start with R. And here they are.

RANA. Rebus. Rhody. Strap in. It’s about to be a heck of a ride.

RANA

Let’s start with Rana. You may never have heard of this word. In fact, it’s not in the North American Scrabble dictionary, so don’t go thinking about using it in your next game. It does have a scientific meaning: Rana is a genus of pond frog. But that’s not what I mean here at all. Here, RANA is an acronym, all in capitals, R-A-N-A. I first encountered this word from my dad over forty years ago, back at the old house on Parkwood Drive in Cobourg, Ontario. Dad used to involve my brother Mike and me in various aspects of his life outside the home. For instance, he used to get me, as a child, to proofread the report cards that his teachers had written for their students, which I can confess now. He’s gone and the statute of limitations has surely passed for what was clearly a privacy violation, even if I did find a lot of mistakes. Similarly, he used to get us to help count the collection money in the old Guild Room at St. Peter’s Anglican Church. Relatedly, once a month or so, he had to call up the folks on his team for sidesperson duties at St. Peter’s, to collect the money that we would later count. Anyway, in Dad’s office at home, there used to be a single sheet of paper, thumbtacked to the bulletin board, with the various names and phone numbers of his team along the rows, and dates as the columns. And in some of the cells of that table, he had written in this cryptic word, RANA, all in capitals. I asked him what it meant and he explained: it’s short for “Right Address, No Answer”. Which made sense – he’s called the person up and moved down the list.

At some point, maybe when I was ten or twelve, I asked not just what it meant, but where it came from. Turns out, RANA was a word Dad learned during his youth, during a period of his life where he, for a time, worked for a collection agency. That’s right – this man, a pillar of the community, was calling up other pillars of the community so they could collect church money, using the same terminology that he used to record his calls to delinquent borrowers to ask them where the money is at, presumably or else some large burly fellow (surely not Dad himself) would show up at their door. It makes me chuckle, the juxtaposition of his misspent youth and his dignified adulthood.

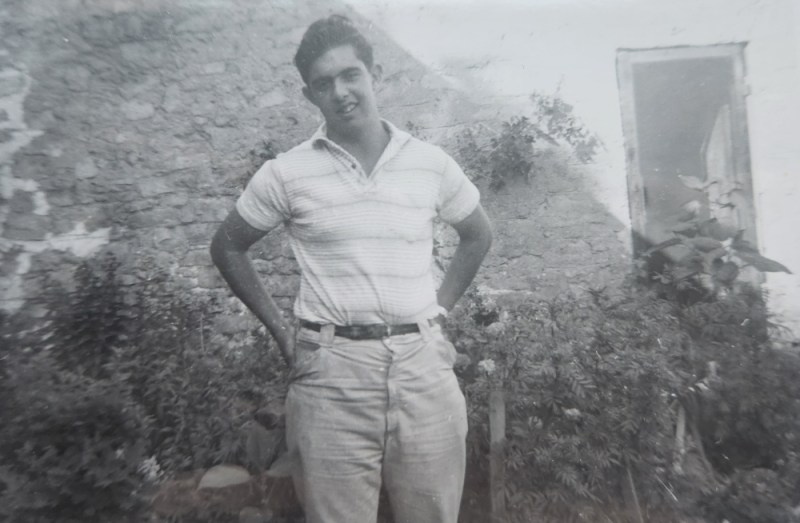

Make no mistake – if you met my dad in, say, 1963, you’d have met a young man who you might think unpromising. Who had been an average high school student at best (I have the old report cards to prove it), tried college at the University of Waterloo, and then, after too many hours playing cards or at the track, dropped out. Who eventually ended up working at General Motors, on the line, which is where he eventually met my mom. Who became a teacher (since you didn’t need a college degree to become a teacher in Ontario in the late 60s, if you knew someone). Who finally went back, through night school and correspondence and weekends spent away, to earn a bachelor’s degree at Trent University in 1974, the year I was born. Who eventually earned a master’s degree in education at Niagara University in New York, which, like my own employer, Wayne State, is one of those border-town schools that serves a lot of Canadians.

Now, if you ask Mom, she’ll say she straightened him out and kept him on the narrow path ever since, through 57 years of marriage. I won’t disagree, mainly because disagreeing with my mother is never a great life choice. But let’s give some credit, too, to Dad. It would be easy to look at that kid marking down RANA at the collection agency and think, well that person is a dud. But that wasn’t the way Dad saw the world. He was a master of seeing the potential in every child, in being unwilling to write anyone off, of his belief in the transformative power of education in all of our lives. It’s a lesson I’ve tried to take into my own heart, into my own teaching, as I carry on his legacy. Even if a kid is ‘right address, no answer’ at the moment, you have no idea who they will become. I know that shiftless young man in 1963 certainly couldn’t have imagined the life, the career, the joys he would have.

Rebus

Now, Rebus. That is a word you might know. If I were in a pedantic mood, I’d tell you that it is a Latin fifth-declension noun in the ablative case. Dad told me, a few years ago when I did some oral history with him, that he always wished he could have studied more classics at college, but that wasn’t the thing that you did, in the 60s, when you were the kid of Greek immigrants looking to not spend your life working in the restaurant. There’s something deeply ironic about not being encouraged to study your own language and culture because it’s not useful enough. So the first time he tried college, he studied science, but when he got to Trent, he took classics whenever he could. He never tried to teach me Latin, but he did once thrust a classical Greek grammar into my hands when I was about nine. The Greek never took, but I did the Latin, for a year or so. Anyway, Rebus. Rebus means “by things”, and is part of a larger phrase: non verbis, sed rebus “Not by words, but by things”. A rebus is the kind of wordplay you get if I drew a picture of a green pea, followed by a tear, to indicate the name “Peter”. You describe it not by words, but by things.

Dad was an avid and lifelong puzzler. Some of my early memories of him were around the table as he looked at the latest issue of GAMES magazine, to watch him and later, to participate with him, in anagrams and crosswords and mazes and brainteasers and wordplay of all sorts, a passion which he passed on to me. Even in the hospital, Dad would bring his various puzzle books with him to help manage the boredom and to keep his mind as sharp as ever. Now, let me take this moment in this public forum to note that while the title passed back and forth over the years, Dad, you are, at this moment, and thus, forever, the Chrisomalis family Scrabble champion. I’m assuming Mike isn’t stupid enough to even attempt to take me on, so my formal concession today should put the matter permanently to rest.

But for Dad, a puzzle or a game wasn’t just something to do on your own, in silence. It was something to puzzle over with your family, with your friends, with your community. It was in that spirit that for many years, Dad ran the annual Frank family Christmas puzzle for all my cousins, which seemed deviously difficult at the time but probably wasn’t so hard. I don’t think any written examples of this tradition survive, but that doesn’t matter. It wasn’t about the winning or losing, but the joy of intellectual pursuits with family, building and reinforcing connections. You show your care for another person – not by words, but by things, and by actions.

Rhody

And that brings us to Rhody. Many of you might know that Dad was musical. He was a longtime member of the Barbershop Harmony Society, and, with his quartet, the Ganaraska Rascals, where he sang bass, became the 1994 Ontario District Novice champion. But before he found barbershop, Dad took up the guitar. Now, in that pursuit, you could say that Dad was a “dedicated amateur” – which for some people, is a nice way to say that he was never very good. That was not the point. But starting in the early 80s, maybe inspired by some of his teaching colleagues who were musical, Dad started to learn on his own, with a cheap acoustic. And so I can still hear him strumming out the chords, sitting around the house, or at the campfire, or wherever: “Go tell Aunt Rhody, Go tell Aunt Rhody, Go tell Aunt Rhody, the old gray goose is dead”. The subject of the folk song is exactly as grim as you might suspect. When you’re a kid you don’t listen much to the words of loss, of mourning. But for Dad it was just about sharing the joy of music, even music he wasn’t very good at. I don’t think there’s any video of Dad playing guitar, but there are plenty on Youtube of him singing barbershop.

But the most important thing about Rhody is not what it is, but when and how it came into Dad’s life. In his childhood and early adulthood, Dad was a music enjoyer but hardly a performer. Dad came to music, first the guitar, and later barbershop, in his 40s, at a time when lots of people are focused solely on career and family. But for Dad, music extended to his family, and to his career. It was a choice to improve himself, to take on a new challenge, even one that he would always admit he was never going to be the best at. And it was a challenge he accepted so that, now, at the end of his life, he would not be the same as he was at its beginning. A life of self-transformation – but not just for himself, but for others. It grew out of his conviction that music – and sharing music – was one of the deepest acts of community possible. He wasn’t doing it just for himself; he was doing it because of his dedication to his students – at Roseneath, Baltimore, and Percy Centennial public schools. His commitment to the arts was a fundamental part of the education he demanded for the students at the rural, not-too-well-off schools that he was privileged to lead. Music may not start with an R but it was, in his view, as important as any of the three Rs for kids whose potential was as-yet unseen.

And throughout his life, Dad was always making himself better so that he could make others better. Even after his retirement, Dad took on new projects, new challenges. Did you know, for instance, that Dad wrote a children’s book, which was never published? Another thing maybe lost to the mists of time. Or that for a few years he served as a member of the community editorial board of the Cobourg Star? That gave him the privilege to write every so often to everyone in the community. Some of those old editorials are still around. I was looking through a couple of them just recently. One of them was entitled “The importance of mistakes” – in which Dad wrote, “We learn from our mistakes and take steps to correct them.” True words from someone who knew a thing or two about mistakes, but never let them define him. And another, suitably enough, was entitled “On teaching the three Rs”, which I’ve included below. It ended with these words that embodied his philosophy: “We need to teach the three Rs but we must also account for the whole child lest tomorrow we find two more Rs – Remorse and Regret.” Dad fought for an inclusive world where every kid had what I had – an environment full, not of remorse and regret, but of words, and music, and love.

Rana. Rebus. Rhody. Three Rs to keep in mind as we enter a world without Peter Chrisomalis in it.