Over the past couple of weeks there have been a number of news stories about the discovery of a new ostracon (pottery shard) from the site of Khirbet Qeiyafa southwest of Jerusalem, bearing five lines of text that have been identified as ‘Hebrew’. The ostracon was dated (through association with burnt olive pits that could be radiocarbon dated) to around 1050-970 BCE, right around where the traditional timeline puts the Biblical King David. The site is a large fortified urban one, and is located in the Valley of Elah, where it is said that David slew Goliath. If the date holds, and if the claim that this is ‘Hebrew’ writing is confirmed, then this would represent the earliest Hebrew writing known to date.

As a teacher I’ve often found it useful to present news reports to students, and ask them how they would evaluate evidence like this in light of what they already know, or to ask what further questions they would want answered before being satisfied. Because most of us (including most scholars) never go any further than the news reports, and because these reports often precede by months or even years the publication of peer-reviewed material, it’s vital to be able to evaluate this material in terms of its implications for archaeology and epigraphy. So what do we know, and how do we evaluate it?

To start with, let’s collect some articles on the subject, which will constitute our body of evidence:

BBC News, 10/30/2008

Associated Press, 10/30/2008

Mail Online, 10/31/2008

Reuters, 10/30/2008

Telegraph, 10/31/2008

New York Times, 10/30/2008

– There are no published results yet, but that’s not unusual in ancient Near Eastern archaeology, which has a fairly conservative perspective on the pace of peer review, but this is a situation where one could get scooped at any moment, so announcing a find early, to be followed up by potentially years of peer review, is not unusual in this area.

– Dating by association is a well-established archaeological technique: if two artifacts are found in the same layer, they are likely of similar age. I have no reason to think the date is off in this case, but we need to recognize right off the top that if the olive pits and the shard ended up in the same layer for reasons other than that they were deposited at around the same time, the date could be way off.

– It is true that this ostracon predates the Dead Sea Scrolls by up to 1000 years, if the dating is right. True, but irrelevant. The Dead Sea Scrolls are frequently invoked in reporting on biblical archaeology as a benchmark for ‘really old Bible stuff’, but in this case, it gives the misleading impression that what has been found is a lot older than other paleo-Hebrew writings, which is simply not the case. The Gezer calendar, which dates to perhaps 925-900 BCE (based on the paleographic style of the text), is the next oldest well-attested Hebrew inscription and is one of many, many paleo-Hebrew texts from the Iron Age in the Levant. This new find extends the history of the script back another 50-75 years, which is interesting – but it has nothing whatsoever to do with the DSS.

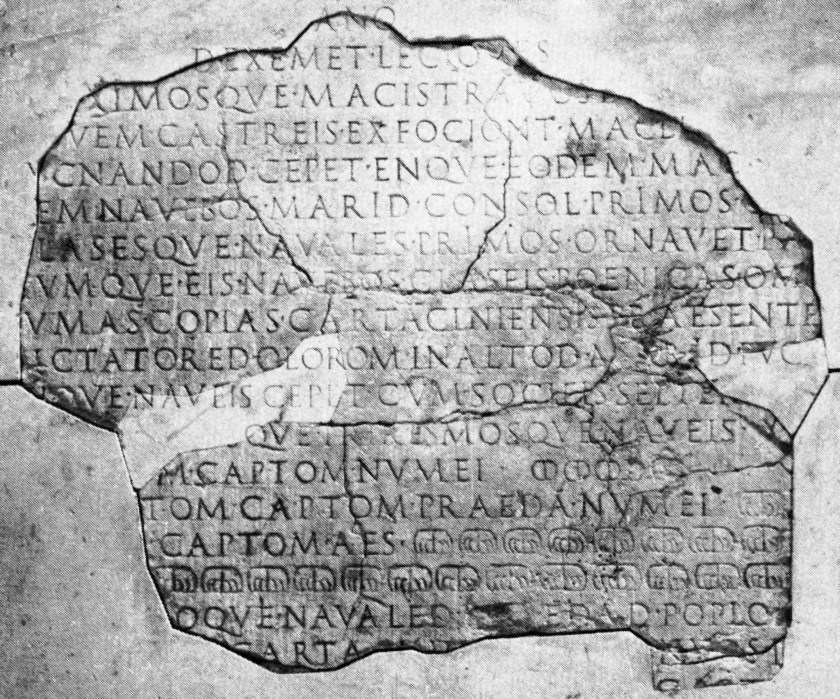

– The claim that this would be the ‘earliest Hebrew writing’ is true but isn’t exactly saying what you think. There are any number of other inscriptions in Semitic languages from this period – for instance, there are Phoenician inscriptions from Byblos dating to around 1000 BCE. The text on the ostracon is apparently in Proto-Canaanite script, of which most of our exemplars are from the late Bronze Age (i.e., around 1500-1000 BCE), used to write any number of ancient Semitic languages, as the BBC article notes. So the script itself is not particularly unusual for the period, and doesn’t tell us anything we didn’t already know.

– And this brings us to a significant issue: the ostracon hasn’t been deciphered yet. So how do we know it’s Hebrew? Well, the BBC tells us, “Preliminary investigations since the shard was found in July have deciphered some words, including judge, slave and king.” and that “Lead archaeologist Yosef Garfinkel identified it as Hebrew because of a three-letter verb meaning “to do” which he said was only used in Hebrew.” This is significant because it identifies the language as Hebrew as opposed to something earlier. This one word on an as-yet incompletely-deciphered ostracon is being used to assert that the writer was a speaker of Hebrew, therefore an Israelite, and therefore that this provides evidence for the Kingdom of Israel in David’s time (e.g. the early 10th century BCE). But we would do well to remember that this is very preliminary stuff. Also bear in mind that our corpus of proto-Canaanite writings is small enough that it is impossible to know whether this form of “to do” was only used in Hebrew, or whether it could have been used in earlier Semitic languages as well.

– The claim is being made by several sources that this ostracon provides evidence for the historicity of King David. Not so. Rather, the claim is that the fact that there is such early writing demonstrates a high level of social complexity and a system of scribal education at the period. If true, this would tend to confirm that there was a large state in Israel in the 10th century BCE, and if one wished to associate that with the Biblical David, one could choose to do so without contradicting the evidence. The presence of words like ‘judge’ and ‘king’ in the text (if confirmed) would provide support for this position from within the text. This stands in opposition to the theory that the Israelites were more egalitarian and disunified at this period, as suggested by the heretofore pretty scanty record from the 10th century. If the latter were true, the Old Testament account would be open to more serious scrutiny; this new find doesn’t confirm the validity of anything Biblical, but rather doesn’t disconfirm it. And remember, this is one ostracon only, not an archive or even a small collection – so we have little idea of what it means. Rollston (2006), who is generally supportive of the argument that there was significant scribal education in Iron Age Israel, discusses many of the complexities behind inferring widespread literacy from the epigraphic/paleographic record.

– On the same topic: Hello, journalists? Could I make a suggestion? Just because you are writing an article about Iron Age Israel and a purported connection with King David does not mean you have to invoke Goliath. Seriously. Especially you, Daily Mail, for citing this undeciphered clay shard as evidence that David actually slew Goliath. At least the Telegraph just presents the theory that the David-Goliath story is a metaphor for Israelite-Philistine conflict at the period.

– One thing that is hardly mentioned is that the ostracon is the longest text in proto-Canaanite script yet attested. This could have important implications for our understanding of the script, once the inscription is read completely. Moreover, once it is read thoroughly, the paleographic letter-forms may actually tell us quite a bit about the date of the inscription, which could tend to confirm or refute the radiocarbon date.

– It would be a mistake to ignore the implications for the historicity of the Iron Age Kingdom of Israel for modern national conceptions and ethnic identity in contemporary Israel. The idea that 3000 years ago, there was a strong, militarily powerful unified kingdom of Israelites in that area has enormous symbolic appeal, and is one of the more controversial issues in contemporary Levantine archaeology. This issue was behind the debate over the tenure case of Nadia Abu El Haj at Barnard/Columbia a couple of years back, centrally concerned with her book, Facts on the Ground (Abu el Haj 2001).

In general, though, the presentation of the data is pretty good and the context of the discussion is generally sane. We have a lot still to learn, and I look forward to seeing the publication of the text in the hopefully not-too-distant future.

Nadia Abu El Haj (2001). Facts on the Ground: Archaeological Practice and Territorial Self-Fashioning in Israeli Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rollston, Christopher A. 2006. Scribal education in ancient Israel: the Old Hebrew epigraphic evidence. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 344: 47-74.