OK, we’ve only had one guess and no correct answers yet on my Doorworks puzzle/contest from yesterday, proving that a) paleography is technically challenging and important and b) I’m cruel and heartless. So, a clue (which regular readers might have guessed already): All four of the ‘words’ are actually numerals.

Doorworks 4: Why paleography matters

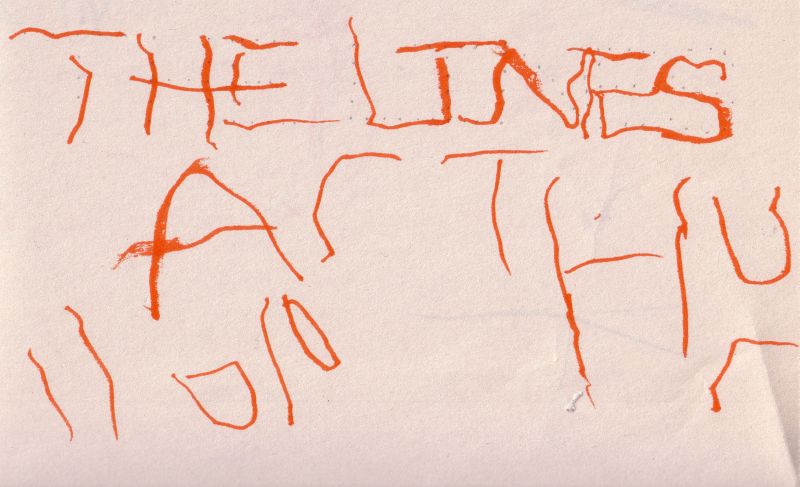

In case any of you were wondering why the study of handwriting matters, and why the elimination of the chair in paleography at King’s College London is a grave loss: Below is an image containing four discrete pieces of late medieval English writing (compiled together as a comparative collection). Can you decipher any of them?

Anyone who successfully deciphers all four may choose a topic or question on which I will write a future blog post.

Clue #1 (02/10/2010): All four words are in fact numerals.

Clue #2 (02/11/2010): They are Roman numerals, each six characters in length.

No country for old tongues

Attn:

Discovery News

BBC News

et al.

We all know how obsessed you are with the oldest of anything. But please, stop. You are doing a grave disservice to languages by saying things like ‘A tribal language thought to have existed for 65,000 years has disappeared forever’ or ‘Languages in the Andamans are thought to originate from Africa. Some may be 70,000 years old.’ This is utter nonsense, even if you find a scholar to tell you otherwise. All languages are always changing, and although some may change more rapidly than others, the idea that a language could persist essentially unchanged for multiple millennia is pure bunk. The idea that we can assign exact ages to languages (other than recent inventions) is even more ridiculous. The only ancient languages are the ones actually spoken in the past, and all currently spoken languages have equally long histories. It is a great tragedy that the Bo language has gone extinct, as it is when, every other week or so, another language goes extinct on this planet. It is a tragedy regardless of how long the language has been spoken, because it represents the end of a particular part of the modern world’s cultural diversity. Your attempt to sensationalize this story by exoticizing indigenous peoples as primitives lost in time is unwelcome and counterproductive. Let me help:

The Bo (Aka-Bo) language was a member of the Northern branch of the Greater Andamanese language subfamily. With its extinction, only one Greater Andamanese language, A-Pucikwar, has any remaining known speakers, and it is highly endangered. The ten Great Andamanese and three South Andamanese languages are all related to one another, although the exact relationships among them remain unclear, but there is no known relationship between the Andamanese languages and any other languages of the world. Their importance for linguistics is that they may represent descendants of the languages of the original migrants to the Andaman Islands many millennia ago, and if we were able to reconstruct the Proto-Andamanese language, potentially to better understand the population and migration history of the Indian Ocean. Their importance for their remaining speakers is inestimably greater.

Juvenile ethnopaleography

Ms. 1 (APTC 1)

Arthur Chrisomalis, The Lines

Construction paper. ff. 2. Unfoliated. 11×8.5 in. Bound at left with four staples. Dated 2010 (?) in hybrid numerical notation (see below).

This manuscript is a juvenile work probably composed on 02/06/2010. There is textual and ethnographic evidence to suggest that the scribe (age 4.5) was aided by a more competent master. Currently the MS is magnetically affixed to the archivum refrigeratum in the scribe’s home.

fol. 1r: Text in orange ink, 3 lines. (Plate 1)

1v: Vertical lines in pencil, crossed with horizontal and diagonal lines in green, pink, red, grey, black, purple, and orange ink. Apparently nonrepresentational.

2r: Vertical lines in pencil, crossed with horizontal and vertical lines in red ink. Apparently nonrepresentational.

2v: Stylized depiction of a smiling human figure in orange ink. Elongated fingers and toes, highly enlarged ears. May be a scribal self-portrait.

Text (fol. 1r)

1. THE LINES

2. ArTHu

3. ||0|0 r

Notes

l. 1: Written in a bold majuscule hand in orange ink. Dotted pencil marks underlying the ink suggest that this line was prepared by the scribe with the aid of a master, an observation later confirmed ethnographically.

l. 2: Written in a hybrid minuscule/majuscule hand; H dips well below the line. Absence of pencil marks and unusual features of the hand suggest that it was composed unaided (confirmed ethnographically).

l. 3: The final character ‘r’ at the right margin seems to be properly attached to the end of l. 2; it is spaced significantly apart from the unusual characters at left. The reading ‘11010’ as an Arabic numeral is improbable given limitations on scribe’s counting abilities. Ethnographic interview with scribe’s assistant/instructor/mother confirms that this is a hybrid notation for the date of composition, 2010. Upon learning of the custom of dating the frontispieces of books from his mother, the author inquired how to do so, and was told, “Put 2-0-1-0”, at which point he wrote the characters ||, then paused and examined the characters. At this point his mother informed him that he could just write the number 2, to which he replied, “That is a 2, in lines.” Thereupon he continued to write the final three characters, noting, however, that the last 0 “is more of an oval.”

One is reminded of the unusual notation developed by Ocreatus in his 1130 Helcep Sarracenicum ‘Saracen Calculation’ which combines the ordinary Roman numerals I, II, III … IX with a circle for O, thus producing a mixed system of the additive Roman numerals and positional Western numerals (Burnett 2006; Chrisomalis 2010: 120). Thus, Ocreatus wrote 1089 as I.O.VIII.IX. Attested in only one MS (Cashel, G.P.A. Bolton Library, Medieval MS 1), this notation represents an effort to incorporate positionality into existing systems of notation, and is related to the debate between the abacists and algorithmists over the proper contexts of use for the newer Western numerals.

Despite the temptation to see in this line a re-invention or re-discovery of Ocreatus’ notation, the ethnographic evidence suggests that this is unlikely. Although the author is familiar with Roman numerals in the context of clocks, the description of the characters || as ‘lines’ rather than ‘numbers’ or ‘Roman numerals’ suggests instead an effort to incorporate tallying principles. It is probable that the Roman numerals derive ultimately from an as-yet unattested Italic practice of tallying used in the 6th century BCE or earlier (Keyser 1988; Chrisomalis 2010: 95-6). Yet tallying is distinct from cumulative-additive numeration like the Roman numerals in that it is produced sequentially as an open-ended count; one cannot simply add signs to the Roman XIII – the equivalent tally might be IIIIVIIIIXIII (Chrisomalis 2010: 15). It is therefore probable that this notation represents the scribe’s attempt to combine the elementary tallying principle of one-to-one correspondence with the familiar Western numerals.

The ethnographic evidence that the scribe paused (as if bemused) upon the production of || might suggest that this form is a scribal error; given, however, that he is conversant with the Western numerals and is capable of producing them unaided, the hypothesis cannot be discounted that the use of || for 2 represents an aesthetically motivated decision. While the title of the work, ‘The Lines’, may refer to the vertical and horizontal lines in fol. 1v and 2r, it may equally be a reference to the lines in the date in fol. 1r.

Works cited

Burnett, Charles. 2006. The semantics of Indian numerals in Arabic, Greek and Latin. Journal of Indian Philosophy 34:15-30.

Chrisomalis, Stephen. 2010. Numerical Notation: A Comparative History. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Keyser, Paul. 1988. The origin of the Latin numerals 1 to 1000. American Journal of Archaeology 92:529-546.

World Loanword Database

The World Loanword Database project (WOLD), edited by Martin Haspelmath and Uri Tadmor, is now online and freely available to users. It’s a remarkable resource compiled with the purpose of analyzing language contact at the lexical level. Over fifty linguists (including my colleague Martha Ratliff here at Wayne State) have provided mini-vocabularies of languages (41 in total) including information for thousands of words on borrowing, attested age, and analyzability, creating cross-linguistic indices that measure the degree to which particular words (and types of words) tend to be borrowed, and from which languages they are borrowed. So, for instance, you can find that more languages have a borrowed word for father than for mother, or that Hawai’ian borrowed several terms for continental North American animals (prairie dog, skunk, kingfisher) from Ute (an indigenous language of Colorado). It’s a rich and highly functional database, and my only ‘complaint’ is that I’d like to see hundreds more languages covered! I need to stop playing with it right now or my day is going to be shot.

Of course, being who I am and doing what I do, the first place I turned was to the numerals, and I immediately noticed two significant things:

– Ordinal numerals seem to be less frequently borrowed than cardinals; first is borrowed less often than one; second less often than two; and third less often than three.

– Fifteen is borrowed less often than five or ten. Fifteen is far more analyzable than either ten or five (most often as ’10+5′) – so how does this make sense?) I’ll have to look at the data more closely to figure this one out … but not today, work calls!