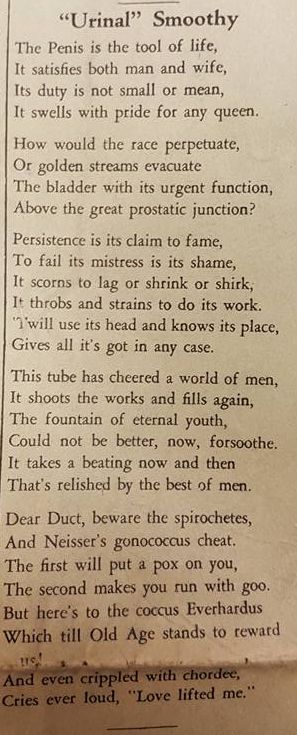

My wife Julia Pope, who is the archivist for the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, came across an unusual item in her collection the other day, an anonymous bawdy poem entitled “Urinal” Smoothy:

The source is the 1933 edition of the program of the Galens Smoker, a yearly student comedy show put on by the University of Michigan Galens Medical Society since 1918 and still going on today. The poem is hardly a masterwork, though clever enough.

The word smoothy (or more often, smoothie) to modern English speakers is a blended thick drink made with fruit. A ‘urinal smoothy’ is downright disgusting, whatever it is. Something had to have changed for this to make sense. And indeed, a look at the Oxford English Dictionary revealed a different, now-obsolete meaning of smoothie:

A person who is ‘smooth’; one who is suave or stylish in conduct or appearance: usu. a man. Occas. with unfavourable sense: a slick but shallow or insinuating fellow, a fop.

1929 Princeton Alumni Weekly 24 May 981/3 Smoothie..indicates savoir faire, a certain je ne sais quoi… Clothes do much to make the smoothie.

This is a sense of smoothie that at least makes a little sense, and fits with the period, but it hardly explains why a poem glorifying the penis would have a title referencing a smooth fellow. But the second quotation in the OED shows us the solution:

1932 B. G. de Sylva et al. (title of song) You’re an old smoothie.

It turns out that “Urinal” Smoothy is just a rather ridiculous pun involving a famous song title from the time. The quotation marks give it away. You’re an Old Smoothie is now largely forgotten, although it was eventually recorded by Ella Fitzgerald in 1958. Here’s an original recording from 1933:

Unfortunately, I don’t think the rhythm of the song fits well with the scansion of the poem, but I like to think that “Urinal” Smoothy was sung to the tune at the Galens Smoker. Of course, it may just have been a poem read aloud.

Smoothie (the stylish man) hangs around for the next several decades but never really takes off. Smoothie (the drink) is first attested only in 1977 but takes off rapidly thereafter and is now widespread, as this Google Ngram attests:

In either case, smoothy with a Y is less common than smoothie. In fact, “Urinal” Smoothy appears to be the first attestation of the less-common spelling smoothy. Google Ngram Viewer won’t help us much here because there are hundreds of optical character recognition errors for smoothly among the results.

I looked around for any additional evidence as to its authorship, but could only find one reference online from an untitled 1943 US Marines songbook containing the poem in its entirety, along with other songs and poems of similar ilk. The poem has been retitled, boringly, The Penis, with “Urinal” Smoothy reduced to a mere parenthetical subtitle. On the other hand, the hit song was a decade old by that time, and the title didn’t make that much sense in the first place. The preface to the songbook mentions several contributors by initials only, including one K.C. from Ann Arbor, Michigan (home to the University of Michigan). Other than a few typographical alterations, the text of the 1943 version is identical to the 1933 one, so we’re presumably dealing with a situation where someone had access to a copy of the text.

So have no fear. The urinal smoothy is neither a new form of frat-boy hazing nor the latest health craze, but the result of a strange confluence of lexical change and 1930s pop culture. Drink from the fountain of knowledge instead!